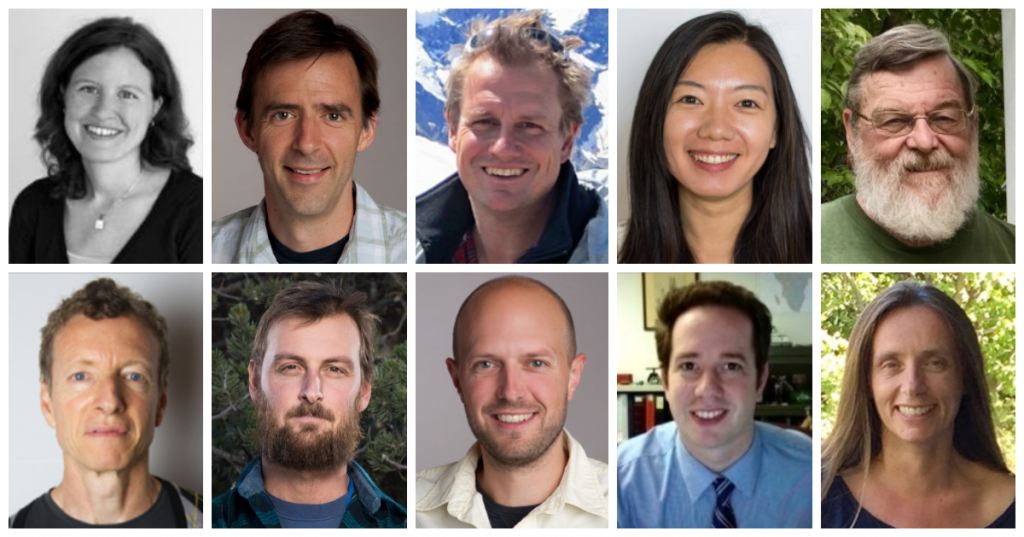

Center for Climate and Life Fellows

The Center for Climate and Life Fellows Program mobilizes Columbia University researchers across disciplines, institutes, and ranks to conduct the vital research needed to understand how climate impacts the security of food, water, shelter, and health, and to explore sustainable energy solutions. This program accelerates the knowledge creation needed to illuminate the risks and opportunities for human sustainability.

Fellows are selected competitively and receive funding at the level of one-third their annual salary for up to three years, with additional funding for research travel and fieldwork.

During FY17 and FY18, the Center awarded $2.1 million in funding to 10 researchers who are bringing a fresh perspective to one of the most pressing issues of our times. These leading scientists are addressing a diverse range of climate questions, from uncovering how past civilizations were influenced by environmental changes to reducing the vulnerability of the global food system to climate-related shocks.

Reflections from our first two Climate and Life Fellows

“In my view, the Center for Climate and Life Fellows Program is one of the most important and effective climate-related programs at Columbia. The fellowship I received has been transformative for my career. I’ve been able to make substantial advances in our understanding of the structure of the global food system and key vulnerabilities, from groundwater depletion to unanticipated trade restrictions. It’s also helped me secure research funding to better understand the links between food security and human mobility as well as the role of artificial intelligence techniques for food systems.” — Michael Puma, NASA GISS

“The Climate and Life Fellowship was the first research funding I received at Lamont. The work it supported led directly to the first-ever estimates of the impact of human-caused global warming on the increase in forest fire area that we’ve seen in the western U.S. over the past several decades. Not only has the wildfire work had a large impact on our knowledge, but it also enhanced my prominence as a scientist, which I believe contributed to my subsequent success at securing research funding for other projects.” — Park Williams, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

Here are some of the ways our Fellows are providing new insights into the impacts of climate change. Visit our website to meet each of our Fellows and learn more about their research.

Improving Tropical Cyclone Risk Assessment

Chia-Ying Lee, a Lamont Assistant Research Professor at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, studies tropical cyclones to learn more about their structure and intensity evolution, and how these are influenced by natural and anthropogenic climate change.

Lee is examining how wind field asymmetries and variability impact tropical cyclone risk and how these can be included in risk models. Her research will result in improved understanding of tropical cyclone risk, allowing societies to better plan for the impacts of tropical cyclones and minimize losses.

Exploring Tropical Forests in a Warming World

Research by scientists like Laia Andreu-Hayles, a tree-ring scientist and Center for Climate and Life Fellow, is helping us understand and respond to climate change. (Photo: Kevin Anchukaitis)

Laia Andreu-Hayles, a tree-ring scientist and Lamont Associate Research Professor at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, received funding from the Center for Climate and Life to collect and develop tree-ring records for tropical forests in Bolivia and Peru. Her project will provide much-needed observational climate data for the region and information about the climate sensitivity of tropical tree species. It will also improve insight into how highly vulnerable tropical ecosystems are changing, and how these changes may affect ecosystem services and water resources on local and global scales.

“Despite the unknowns about what we might find, we know our results will be interesting and it’s going to add a lot of information to what we know about trees in the tropics, so I’m grateful to receive funding from the Center for Climate and Life for this research,” Andreu-Hayles said.

Understanding Earth’s Geologic History

Pratigya Polissar, an organic geochemist at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, is mapping vegetation history using molecular fossils to examine how climate shapes Earth’s ecosystems. As part of the project, he’ll compare recent vegetation histories with existing records of climate to illuminate the contributing factors to particular vegetation transitions.

The likely culprits for these defining events were a combination of changing temperature, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, and the distribution of rainfall—all parameters being altered today due to greenhouse warming. His findings will help map out how ecosystems and human food supplies may be affected in the near future.

Bridging the Gap Between Weather and Climate

Andrew Robertson is a Senior Research Scientist and head of the Climate Group at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society. He’s creating a real-time forecasting system, sub-seasonal to seasonal (S2S), that can predict sub-seasonal weather and climate fluctuations for the time period of about a week to a month ahead.

The forecast will be issued each week in a probability format relevant to the risk of floods, droughts, heat and cold waves, and other societal impacts. Being able to forecast this range will provide essential early warnings that can help societies adapt to and become more resilient to the effects of climate change.

“The funding from the Center for Climate and Life has helped me greatly by allowing me to devote more energy to advancing my work on S2S forecasting. It helps me fulfill my role as co-chair of the World Weather & World Climate Research Programmes’ S2S project, an effort that has stimulated a lot of research activity in this new forecasting range in the past few years,” Robertson said.

Illuminating Greenland Ice Sheet Instability

Eastern Greenland. (Photo: NASA IceBridge/Jefferson Beck and Maria-José Viñas)

Joerg Schaefer and Gisela Winckler, geochemists at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, are developing a more detailed picture of the past, present, and future of the Greenland Ice Sheet. The goals of their project are to produce the first comprehensive direct record of the past dynamics of the Greenland Ice Sheet, an update on sea level predictions and the first analysis of its impact on societies.

This project builds on their recent research, which indicates that Greenland was nearly de-glaciated for extended periods of time around two million years ago and makes the case that the Greenland Ice Sheet is highly vulnerable to climate change.

“It’s really important that frameworks like the Center for Climate and Life exist right now. Climate change is a completely interdisciplinary problem. The older and more experienced you get as a scientist, the more interested you become in actually connecting to the solutions side. The Center helps us do that,” Schaefer said.

Using Tree Ring Records to Decode Earth’s Climate History

Ed Cook is one of the founding directors of the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory Tree-Ring Laboratory. During his 43 years at Lamont, Cook has used tree rings to decode past climate patterns and advance understanding of drought. Part of his work is devoted to developing “drought atlases” or extensive, centuries-long records of wet and dry periods for a given region, derived from the data contained in tree rings. He and his colleagues published the first of these, the North American Drought Atlas, in 2004, followed by the Monsoon Asia Drought Atlas, published in 2010, and the Old World Drought Atlas and Eastern Australia and New Zealand Drought Atlas, both published in 2015.

Cook received funding from the Center for Climate and Life to develop a much more comprehensive Northern Hemisphere Drought Atlas, which will add to what we know about the causes of drought, how it impacted people and the environment in the past, and what its impacts might be in the future.

Fellows and Affiliated Scientists in Action

Billy D’Andrea and graduate student Lorelei Curtin prepare to collect a sediment core in Rano Aroi, Rapa Nui. (Photo courtesy of Billy D’Andrea)

In March 2018, a team of scientists led by William D’Andrea collected sediment cores from the wetlands of Rano Kau, Rano Raraku, and Rano Aroi on Easter Island. These geologic records likely span the past 30,000 years and will be used to examine various aspects of climatic, environmental, and human land-use history.

Also in March 2018, Brad Linsley and his research team recovered coral cores from an area in the Gulf of Chiriquí, on the Pacific coast of Panamá. Linsley is using the cores to reconstruct the history of coral bleaching and hydrologic changes in the region back to the mid-1800s. His results will ultimately improve understanding of seasonal and decadal-scale changes in rainfall in Central America.

Chia-Ying Lee, a scientist who’s breaking new ground with her research on tropical cyclones, explained in a video the role climate change may have played in Hurricane Harvey becoming one of the most intense and costliest storms in history.

Michael Puma and his colleagues made a critical discovery related to the resilience of the global food system. In a Nature paper, they explored how global food consumption is linked to the alarming rates of groundwater depletion worldwide: Approximately 11 percent of non-renewable groundwater used for irrigation is embedded in international food trade. These findings reveal some countries are particularly exposed to food insecurity because they both produce and import food irrigated from rapidly depleting aquifers.

Park Williams co-organized a three-day conference on fire prediction at Columbia University, which brought together more than 100 scientists, fire land managers, insurance industry representatives, and many others from around the world who share the goal of advancing the science of fire prediction. Among the speakers was Center for Climate and Life Fellow Andrew Robertson, who presented his research on seasonal fire prediction.